Many thanks to Nantucket Preservation Trust board member Michelle Elzay for sharing this special guest blog post.

It has been a month of dinner parties. Set at a long wood table beside a fire that is always hard to start but has a glowing coal bed by the end of the night. The first night we had roast chicken and toasted our friend’s birthday. We had planned a weeklong spring break visit to Nantucket with another couple. But as the Covid-19 pandemic took hold, it became clear that we should remain on the island. A week has spread to four, with no set date to leave. Houseguests have become roommates.

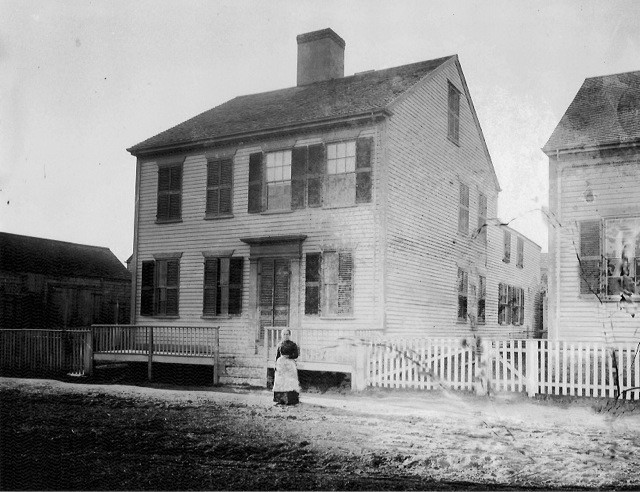

I am staying in a house that a partner and I restored five years ago. This house, on Union Street, was built in 1834 by prolific island builder John B. Nicholson. Before our preservation, the house had not been lived in since World War II. Though in need of extensive repair, the interior of the house stood intact as it was built almost two centuries ago. It struck me, after a few days of “shelter in place,” that the rhythm of how I was spending my time in this house might not be unlike those of the people who occupied it at the time of its construction.

The square block bounded by Union Street, Orange Street, Maiden Lane (now York Street), and Dover Street was developed in the 1830s largely by John Nicholson. Before that, four small homes had stood on the block. By 1836 Nicholson had added at least eight homes, two since removed, turning what was a more rural and African American part of Nantucket “Newtown” into a dense nineteenth-century urban environment.

In this new Newtown of larger homes, households shrunk from multi-generational families with cousins and extended relatives living together to smaller family units. A previous owner of this property, whose house was either recycled or removed, was an African American man named Essex Boston. At the time of the 1810 census he was in his seventies and headed a household of ten. He had worked as a cordwainer and yeoman, outside of conducting extensive real estate deals, a foreshadow of Nicholson’s career. Nicholson’s new client base consisted mostly of white master mariners and their families, although their relatives still lived close by. Our house was built for mariner Charles Andrews and his wife Eunice. In 1836 Eunice’s cousin, Jethro Gardner, purchased the neighboring Nicholson house to the south, since removed. While these men’s maritime careers took them on multi-year journeys away from Nantucket, life on the island was largely conducted from home. Looking back, it is clear the architecture of these houses was intended to enable extensive time at home. Now, it makes sheltering in place pleasurable.

Nicholson’s signature building style is a typical two-story Nantucket house with four bays. He also built many slightly smaller story-and-a-half houses with Greek Revival details similar to the larger homes. In the 1830s these houses were built with a rear el that functioned as the service and kitchen portion of the home. The yards were too small for farming but contained large cisterns for water and a well. Both style houses have three rooms and a hall formed around a central chimney mass at both stories. Living in these houses feels a little like moving through the circular pattern of a shell—you walk though rooms, rather than halls, to get to another room. No room feels shut off from the rest and none go unused. They were designed for warmth, both literal and figurative.

In the 1830s front parlors were often reserved for important guests or business transactions. There are multiple locks on the door to the middle room, now our dining room, and the front parlor. The hall was a place to wait, but also a place to perform what I image to be lesser business transactions. The locks are the hints of past commerce. Many women on Nantucket took up small businesses to bring in household income while their husbands were away at sea. This helped avoid the need to use credit at the markets and also afforded some women a level of independence not typically available to those on the mainland until a century later. The house was both a place of shelter and a place of commerce, and also, in my mind, a place of freedom.

I have turned a small attic room, rumored to have been framed out to shelter stranded sailors, into my design and art studio and writing room. Writing from a little desk perched near a window with a springtime view of the harbor, I willingly strand myself half in and half out of another time. The pacing of time during the stay at home order has both slowed and sped up. During the day our household retreats to various rooms to work. They appear in the kitchen for meals and then we all come together for what is our main meal of the day, dinner, in front of the fire in the middle room.

Days pass quickly in the rhythm of domestic routine, with less accomplished than during my usual rush from job to job, store to office and exercise. Working from home is parceled between domestic tasks and what feels like an endless yet pleasurable cycle of cooking. There is also a slowness to the rhythm, with sunny springtime conversations in the yard supplanting a rush to work. Deadlines have become abstract. The season unfurls slowly day by day. Birds nest and chatter; buds form on trees, then suddenly erupt in pink. You feel both connected to and isolated from your neighbors, who remain unseen but hinted at—a light flicks on, a cat sits on a window sill.

My partner in the preservation of the Union Street house lives next door. We chat in the warm spring sunshine in her yard and rake leaves left over from the fall. Illness and death are a part of our daily conversation. They press in around us, but also have been absent from the safety of this household.

Illness is never planned. I think it is human nature to believe that life will be long. Charles Andrews, despite a career of dangerous ocean voyages, died at home in 1839 of a virus, tuberculosis. It was June. I imagine Eunice’s lonely grief and uncertain future in the beautiful new house they had moved into just five years before. Because Charles died intestate, Eunice had to appeal to the courts for the right to inherit this house and retain custody of her three sons. After winning her claim in 1842, she sold the house to a neighbor, David Smith, and in turn purchased Smith’s house. That one-and-a-half-story home was on Maiden Lane, just on the other side of her cousin Jethro Gardner. She and her sons remained there, within an arm’s length of their old home.

Almost two hundred years later, I shelter in place at that same spot with a small community. Friends who were guests become like family, and others are just next door. As the days go by, all our stories become woven within the walls of the past.